Ehlers-Danlos

Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of hereditary disorders characterized by varying degrees of soft connective tissue fragility, affecting mainly the skin, ligaments, blood vessels, and internal organs. Cardinal features are joint laxity and skin alterations that include hyperextensibility, scarring, and easy bruising. The prevalence of EDS is estimated to be approximately 1 in 5,000 births; however, the incidence rises with increased physician awareness (1). The European Union defines a rare disease with a prevalence of less than 50 in 100,000, thus the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes count as such.

Name givers of the EDS were Edvard Ehlers (Copenhagen) and Henri-Alexandre Danlos (Paris), two dermatologists who clinically recognized the condition at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1988 the “Berlin Nosology” portrayed 11 subtypes of EDS, then characterized by Roman numerals, based on clinical findings and mode of inheritance. (2) The declaration of the molecular and biochemical basis of many of these EDS types – most are related to disturbance of the fibrillar collagen types I, III, V – led to a revised classification known as the “Villefranche Nosology” published in 1998 (3). This Nosology recognized 6 subtypes containing the classical, vascular, kyphoscoliotic, dermatosparaxis, hypermobile and arthrocholasis subtype. Major and minor clinical criteria including the biochemical and molecular basis were elucidated and the Roman numerals were substituted by a descriptive name regarding the manifestations of each type. Nonetheless, whole spectrums of novel, clinically overlapping, rare EDS-variants have been delineated with the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) since. Mutations have been identified in a bunch of new genes, which are not always, at first sight, involved in collagen biosynthesis and/or structure. These advances have now made it possible to diagnose the causative mutation for patients presenting these phenotypes (4,5). Hence, an international EDS consortium recommended an adjusted classification consisting of 13 subtypes as outlined in the following table (4).

EDS Classification

| New nomenclature 2017 | Villefranche Nomenclature 1998 | Former nomenclature / other names | Gene | Protein | Inh. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical EDS (cEDS) | Classical type | Gravis, EDS I Mittis, EDS II | COL5A1 COL5A2 COL1A1 | Type V collagen Type I collagen | AD |

| Vascular EDS (vEDS) | Vascular type | Arterial ecchymotic EDS IV | COL3A1 | Type III collagen | AD |

| Periodontal EDS (pEDS) | EDS periodontitis EDS VIII | C1R C1S | C1r C1s | AD | |

| Arthrocholasia EDS (aEDS) | Arthrocholasia type | Arthrochalasis multiplex congenita, EDS VIIA, EDS VIIB | COL1A1 COL1A2 | Type I collagen | AD |

| Dermatosparaxis EDS (dEDS) | Dermatosparaxis type | Human dermatosparaxis, EDS VIIC | ADAMTS2 | ADAMTS-2 | AR |

| Classical-like EDS (clEDS) | TNXB | Tenascin XB | AR | ||

| Kyphoscoliotic EDS (kEDS) | Kyphoscoliosis type | EDS VI EDS VIA | PLOD1 FKBP14 | Lysylhydroxylase 1 FKBP22 | AR |

| Musculocontractural (mcEDS) | Adducted Thumb Clubfoot syndrome EDS Kosho type D4ST1 deficient EDS | CHST14 DSE | Dermatan-4-sulfotransferase 1 Dermatan sulfate wpimerase 1 | AR | |

| Myopathic EDS (mEDS) | COL12A1 | Collagen XII | AD/AR | ||

| Spondylodysplastic EDS (spEDS) | EDS progeroid type | EDS progeroid, β3GalT6-deficient EDS, Spondylocheirodysplastic EDS | B4GalT7 B3GalT6 SLC39A13 | Galactosyltranserase I and II ZIP 13 | AR |

| Brittle Cornea Syndrome (BCS) | Brittle Cornea Syndrome | ZNF469 PRDM5 | ZNF469 PRDM5 | AR | |

| Cardiac valvular EDS (cvEDS) | Cardiac valvular EDS | COL1A2 | Type I collagen | AR | |

| Hypermobile EDS (hEDS) | Hypermobile type | Hypermobile, EDS III | ? | ? | AD |

Common signs and symptoms of the Ehlers-Danlos Syndrom

Although all the clinical aspects described below differ in their degree to each one of the subtypes they are listed together for they appoint to a lot of different types of EDS.

Dermatological aspects

A cardinal feature of EDS, except for vascular and periodontal EDS (types IV and VIII), is the cutaneous hyperextensibility. Following easy extension the skin snaps back after release. In adults loose folds of skin may appear over the elbow joints (Figure 1 “c“), palms may be distinctively wrinkled and the feet soles appear loose-fitted like oversized socks. This seems to be the result due to loose attachment of the skin with the subcutaneous tissues.

Dermatorrhexis (cutaneous fragility) is displayed after minor trauma over pressure points such as knees or elbows, with splitting of the dermis of mucosa. These wounds present a ‘’fish-mouth’’ like appearance with gaping. The ability of wound healing is delayed and after successful primary healing the stretching of scars is typical for all EDS types. The scars appear wide, thin, and shiny comparable to ‘’cigarrette paper’’ or ‘’burn scars’’ (Figure 1 “b“ and “d“). As a result of repeated traumata these scars become darkly pigmented.

Hematoma and bruising. Due to the fragility of the perivascular connective tissue as well as the walls of the small blood vessels bruising is common in patients suffering from EDS. Bleeding of the gums after tooth brushing and not ending bleeding after tooth extraction are frequent.

Molluscoid pseudotumors and spheroids. Molluscoiud pseudotumors present themselves as fleshy, heaped-up lesions with scars over pressure points such as knees and elbows (Figure 1 “c“). Spheroids are characterized as small, cyst like nodules with easy movablity in the subcutis over the bony prominences of the legs and arms. They appear in about 33 % of the patients and feel like hard grains of rice. These spheroids are former subcutaneous fat lobules that have become fibrosed and calcified after the loss of blood supply.

Other dermatological features such as hyperkeratosis follicularis; piezogenic papules, which are painful but reversible herniations of adipose lobules through the fascia into the dermis; a lack of striae gravidarum, which represent focal tears in the dermis horizontal to the direction of stress but not disturbing the epidermis (5).

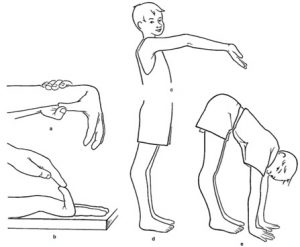

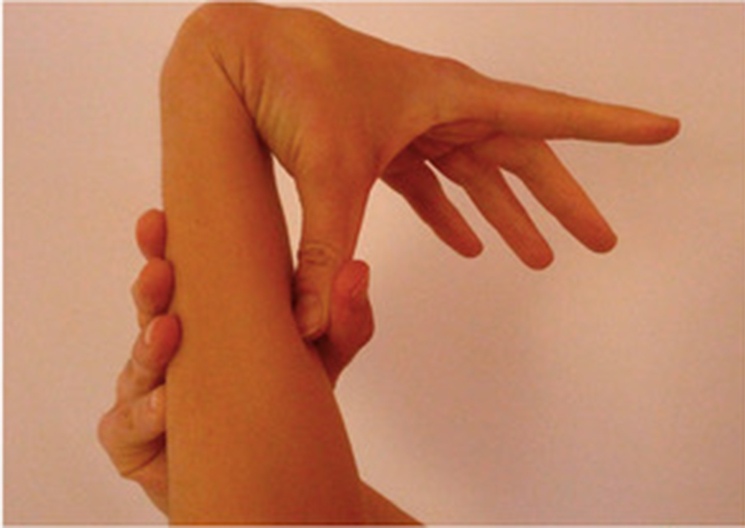

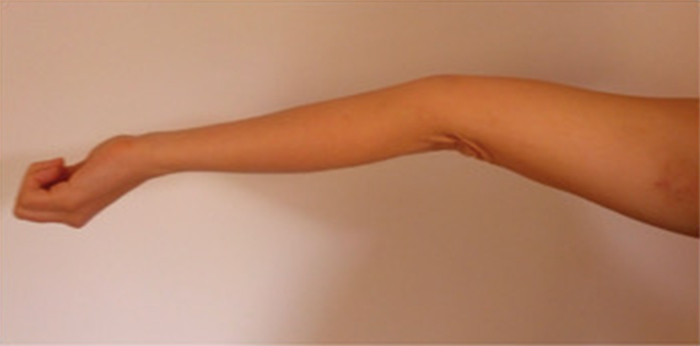

Following patient pictures are provided to show an example of cutaneous hyperextensibility:

Orthopedic aspects

Pes planus, joint dislocations, spinal deformity, joint effusions, thoracic cage deformity, osteoarthritis, talipes, and congenital hip dislocations are the most significant orthopedic abnormalities ordered from high to low frequency of appearance.

Hyperextensibility or hyperlaxity of joints which is also known as ‘’hypermobility’’ of the joints due to laxity of the joint capsules, ligaments, tendons, and musular hypotonia. Joint laxity is generalized influencing both minor and major joints (expect EDS IV). The ‘’Beighton-score’’ has become the accpeted screen for diagnostics of joint hypermobility (Figure). For more information about the Beighton-score please see diagnosis.

Disclocations. Most common habitual or occasional dislocation joints are the shoulder, patella, digits and thumbs, hip, radii, and clavicles (6) with the frequency being proportional to the extend of joint laxity. These disclocations may be the result of a simple everyday movement, for example putting on a coat or raising an arm during school class and hereby dislocating the shoulder.

Joint effusions. They are proportional to activity and appear mainly at the end of the day. Affecting primarily weight-bearing parts they can be recurrent or persistent. Mostly affected joints are knees, ankles, elbows, and digits in decreasing order. This is again proportional to joint laxity.

Joint instability. As a consequence of lax ligaments and poor muscle tone it is hard for children to control their unstable limbs resulting in easy falling and tendency to walking late. A result of joint instability the Osteoarthritis is a major issue with the main complaints concentrating on knees, hands, ankles, general joints, and shoulder.

Patients are often confronted with Bursae in the olecranon and prepatellar region, these have to be distinguished from hematoma or molluscoid pseudotumors as mentioned above.

Bones tend to fracture due to a low bone mass and abnormal bone structure. Osteopenia is a constant feature of EDS VI, VIIA, VIIB, and VIIC (EDS VII is also known as the arthrocholasia type in the new classification).

Chronic joint and limb pain is a common complaint although skeletal radiographs appear normal. Pain, swelling, dislocation of joints, surgical history, and impaired ambulation seem to be more frequent and pronounced in patients with EDS III (hypermobile type) than in those with EDS I, II (both classical type) and IV (vascular type) (5).

Following patient pictures are provided to show hyperextensible joints:

Pregnancy, Obstetric, and Gynecological Features

A woman suffering from EDS takes a certain risk when becoming pregnant for herself as well as the newborn. For the mother the risk of gross abdominal hernia and spinal deformity with backache is increased and cervical insufficiency can lead to miscarriage as well as premature birth. Complications for the fetus include prematurity and prenatal rupture of the membranes. The fact that fetal membranes are affected to the same extent as the fetus was demonstrated by Barabas AP et al, 1966 when 14 out of 18 children with EDS were premature and 13 of these had premature rupture of membranes, with normal siblings never being premature (5).

Gastrointestinal Complications

In general the complaints affecting the gastrointestinal region can be subdivided into reactions to tissue extensibility or reactions due to tissue fragility. This group consists of gastric, duodenal, and colonic diverticula, visceroptosis, gastric atony, megaesophagus, and megacolon. A common complaint is constipation which is probably a consequence of the flaccidity of the large bowel. Typical problems of classical and hypermobile EDS are gastroesophageal reflux and ittitable bowel syndrome.

Inguinal and umbilical herniae are frequent and can reoccur even after surgical correction (5).

Neuromuscular and psychological features

Muscular hypotonia in the newborn, and especially the premature, has a high frequency and can be so harsh that breastfeeding is impossible so these children need special feeding bottles with larger holes.

Joint hypermobility and hypotonia may be the reason for delayed motor development, delayed walking or frequent stumbling as well as mild motor disturbance (”clumsiness”) in children.

Other common complaints are fatigue or muscle cramps in the calves at night. The most harsh neurological complications however are the ones resulting of intracerebral hemorrhages. For example transient aphasia or amaurosis, and hemiplegia or fatal stroke-like caused situations by multiple arterial aneurysms or arteriovenous fistulae as typical findings of EDS IV (vascular EDS). Yet structural cardiac abnormalities, such as mitral valve prolaps or tricuspid valve prolaps, are rather chance associations and therefore rare (5).

Ophtalmological aspects

In an array of 100 patients Mühlendyck H et al., (1978) showed that extraocular signs are common. 27 patients had epicanthic folds, seven had blueness of the sclerae, seven had strabismus and eight had myopia. Ocular signs are not frequent and include keratoconus, which is defined as thinning of the central part of the cornea and forward bulging (7).

Oral manifestations

Fragile oral mucosae, with easy bruisability and hemorrhagic blisters as well as bleeding gums are typical oral aspects. The teeth are often crowded but otherwise normal. Histologically abnormalities such as irregular and ill-formed secondary dentinal tubules, vascular dentinal inclusions, and fibrinoid gingival deposits are described (5). More oral manifestations will be described below.

Other features

Typical for EDS IV (the vascular type of EDS) are hemoptysis, hematothorax, and spontaneous and recurrent pneumothoraces, with or without mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema (8).

The urinary tract is affected mainly by anatomical irregularity such as urinary bladder diverticula which are usually asymptomatic. Vesico-ureteral reflux can lead to urinary tract infections and renal insufficiency (9).

Genetic basis

Up to now, mutations in 20 genes have been found to cause the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Causative mutations were found either in genes coding for collagens or collagen processing enzymes.

As an example considering classical EDS it is the COL5A1 or COL5A2 gene that are primarily mutated in turn affecting the protein type V collagen. Mutations in COL5A3 have also been described in classical EDS. The α3 chain is primarily responsible for developing muscles, ligaments to form bones and in joints (10). Mutations in COL1A2 and COL1A1 coding for type I collagen are causative for the cardiac-valvular type and the arthrochalasia type. For the vascular type of EDS the COL3A1 gene is the most common mutation affecting collagen type III. COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1, COL5A1, and COL5A2 are coding for pieces of several different types of collagen. These pieces assemble to form mature collagen molecules that give structure and strength to connective tissues throughout the body (47).

Other genes – including ADAMTS2, FKBP14, PLOD1, and TNXB, mutations in which are causative for the dermatosparaxis type, classical-like type, and kyphoscoliotic type – provide instructions for making proteins that process, fold, or interact with collagen. Mutations in any of these genes disrupt the production or processing of collagen, preventing these molecules from being assembled properly. These changes weaken connective tissues in the skin, bones, and other parts of the body, resulting in the characteristic features of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (47).

In most people with hypermobile EDS, the cause is unknown.

For more information refer to genetic causes.